The engine low-pressure oil pipe is a critical yet often overlooked component that delivers oil from the sump or external reservoir to the oil pump inlet—operating at pressures typically below 15 psi. A cracked, corroded, or improperly sealed low-pressure oil pipe can cause oil starvation, leading to catastrophic engine failure within minutes, even if the rest of the lubrication system is intact.

Unlike high-pressure oil galleries that feed bearings and camshafts (which operate at 40–80 psi), the low-pressure circuit relies on suction and gravity. Its integrity depends on airtight seals and structural rigidity to prevent air ingress—a condition known as “cavitation”—which disrupts oil flow and damages the pump.

Location, Function, and System Integration

In most internal combustion engines, the low-pressure oil pipe runs from the oil pan pickup tube to the oil pump’s inlet port. In dry-sump systems—common in performance and marine engines—it connects the remote oil tank to the pressure pump. The pipe must maintain a continuous column of oil; any leak introduces air, reducing volumetric efficiency and causing erratic oil pressure readings.

Modern designs often integrate a strainer or anti-drain valve at the pickup end to prevent debris entry and oil drain-back during shutdown. The pipe’s internal diameter (typically 12–20 mm) is carefully calibrated to balance flow rate and velocity—too narrow causes restriction; too wide reduces suction velocity, increasing cavitation risk.

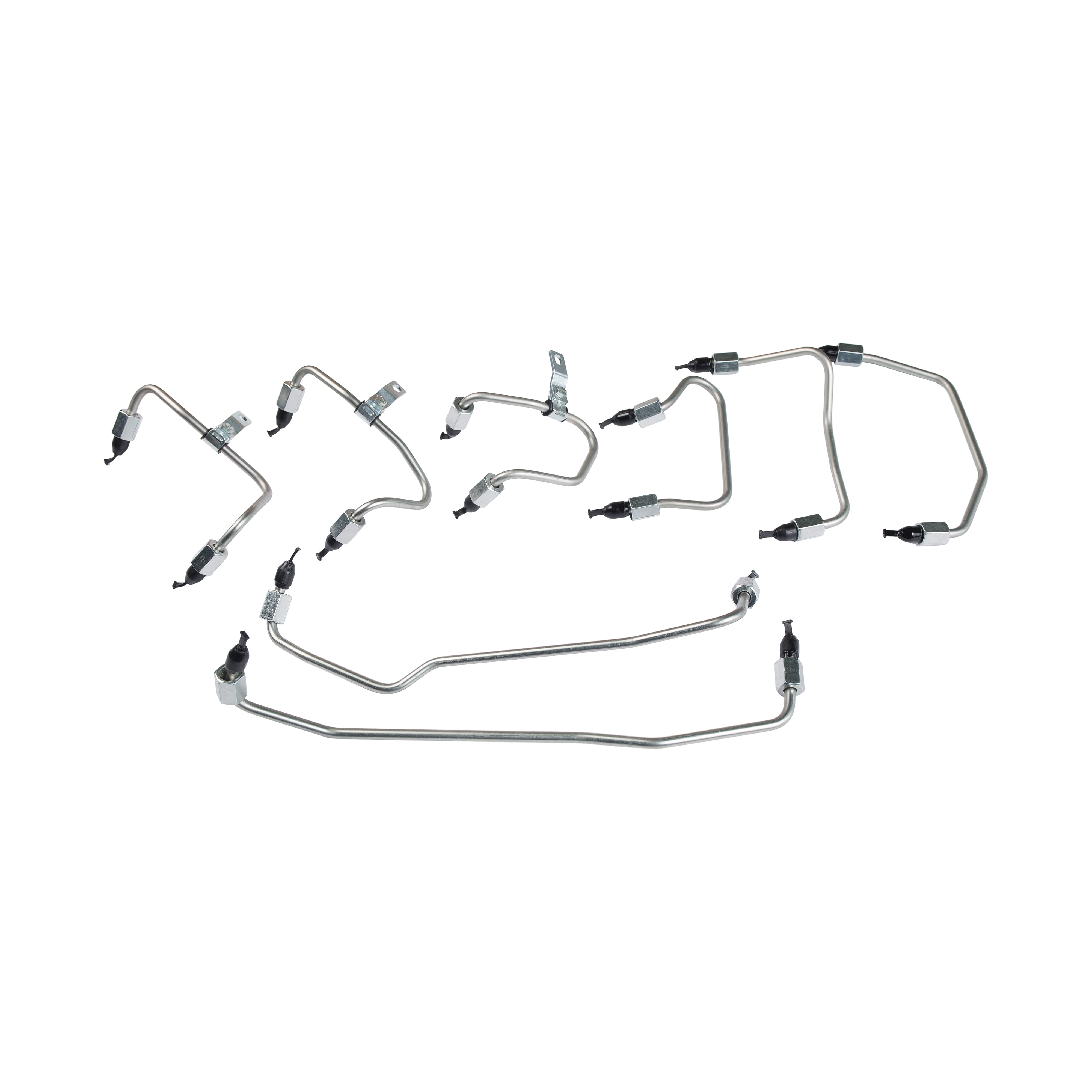

Common Materials and Construction Types

Material choice depends on engine type, environment, and cost:

| Material | Typical Application | Max Temp | Key Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steel (Seamless) | Heavy-duty diesel, trucks | 150°C | Corrosion if uncoated |

| Aluminum Alloy | Performance cars, motorcycles | 120°C | Fatigue cracking at bends |

| Reinforced Nitrile Rubber | Marine, vintage engines | 100°C | Permeation, ozone degradation |

Steel remains the most reliable choice for high-vibration environments, while aluminum offers weight savings in racing applications where maintenance intervals are short.

Failure Modes and Diagnostic Signs

Low-pressure oil pipe failures rarely announce themselves until it’s too late. Common symptoms include:

- Fluctuating oil pressure at idle or during acceleration

- Whining or whistling noise from the oil pump (indicating air ingestion)

- Visible oil leaks near the oil pan or pump flange

A simple test: remove the oil filler cap and observe the rocker arms—if they appear dry despite adequate oil level, suspect a suction-side leak. Pressure testing the low-pressure circuit with a vacuum gauge can confirm air ingress (>2 inHg vacuum loss in 30 seconds indicates a breach).

Installation Best Practices and Seal Integrity

Proper installation is non-negotiable. Flange joints must use OEM-spec gaskets or O-rings—never RTV silicone alone, which can extrude into the oil stream. Bolt torque should follow manufacturer specs; under-torquing causes leaks, while over-torquing cracks aluminum housings.

For rubber hoses, use double-wire clamps (not single-band) and ensure no kinks or sharp bends. The pipe must be supported every 150–200 mm to prevent vibration fatigue. After reassembly, prime the system by cranking the engine without ignition (or using a pre-lube pump) to purge air before startup.

OEM vs. Aftermarket Replacement Considerations

While aftermarket pipes are cheaper, they often cut corners on wall thickness or material grade. A 2022 study by an independent automotive lab found that 38% of budget aftermarket oil pipes failed burst tests at 30 psi—well below the 60 psi safety margin required by OEM standards.

Always verify material certification (e.g., ASTM A519 for steel tubing) and dimensional accuracy. For high-performance or commercial vehicles, OEM or premium-brand replacements (e.g., Mahle, Gates, or INA) are strongly recommended to avoid premature failure.

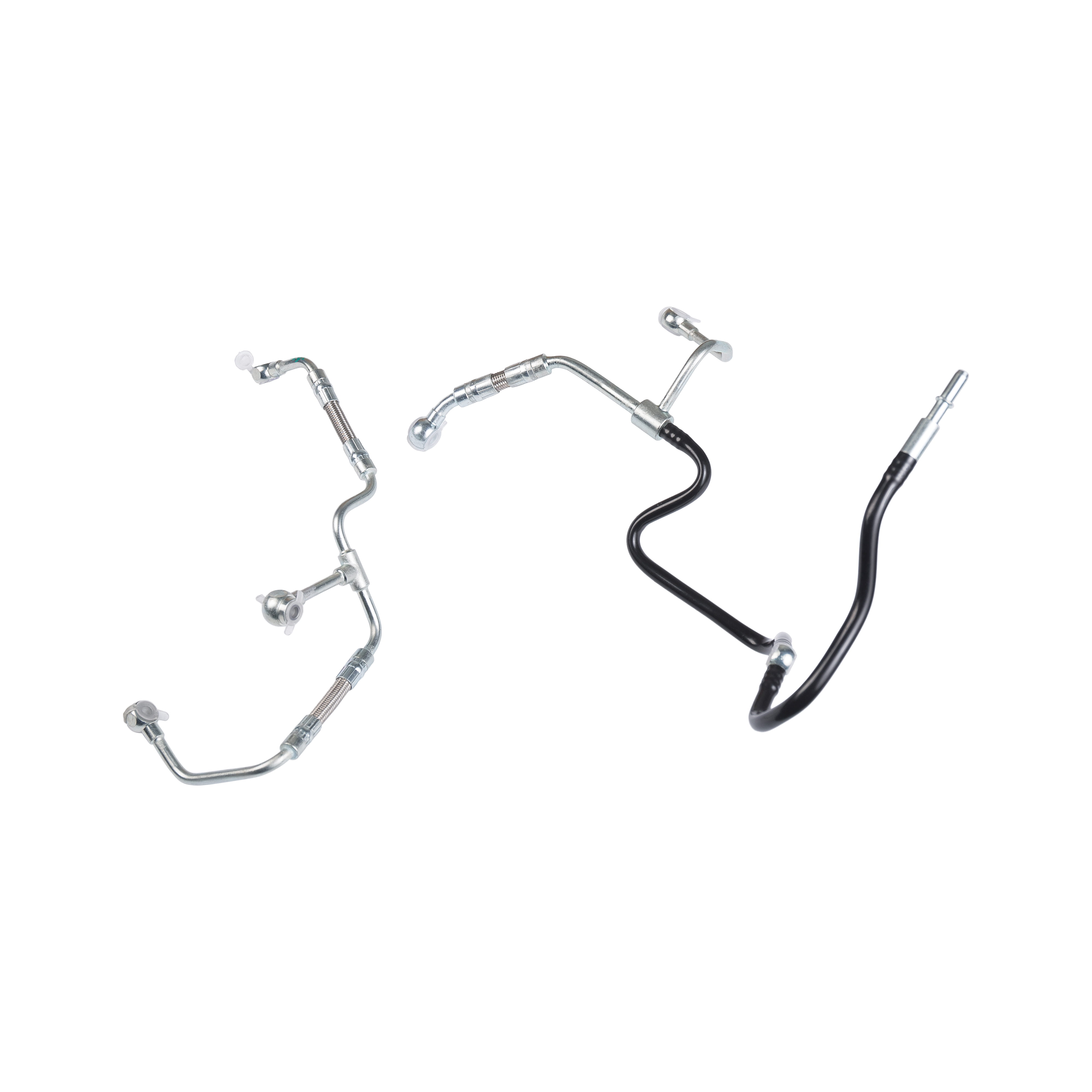

Special Considerations for Dry-Sump Systems

In dry-sump engines—used in race cars, helicopters, and some luxury SUVs—the low-pressure circuit includes multiple scavenge lines returning oil to the tank. These pipes operate under slight vacuum and are prone to collapse if made from thin-wall or non-reinforced materials.

Use only braided stainless steel or reinforced PTFE hoses rated for vacuum service. Ensure all fittings are AN-style or JIC to prevent thread stripping. Even a small leak in a scavenge line can cause oil aeration in the tank, leading to foam-induced oil pump cavitation and bearing wear.

Preventive Maintenance and Inspection Intervals

Include the low-pressure oil pipe in routine inspections—especially after off-road use, engine overheating, or oil changes. Check for:

- Cracks at weld seams or bends (use dye penetrant for aluminum)

- Corrosion pitting on steel pipes near the oil pan rail

- Hardening or cracking of rubber sections due to oil additive exposure

Replacing the low-pressure oil pipe during major engine work is a low-cost insurance policy against sudden lubrication failure. Given its role as the engine’s first line of oil delivery, its reliability should never be assumed.

English

English Español

Español русский

русский